Poids Raw vs. Cours Jette #

Challenge #

- Difficulty: difficult

- Value: 989 pts

- Authors: @OwlyDuck & @Lowengeist

- Files: memory.7z

Cette série de challenges implique un scénario d’attaque mettant en œuvre des programmes qui peuvent potentiellement nuire à vos équipements, nous faisons appel à votre vigilance pour toute forme d’analyse dynamique

Bienvenue chez Entreprendre !

Nous sommes une entreprise jeune et dynamique spécialisée dans les poids. Si vous appréciez observer des boulets se projeter, enfin se faire projeter, venez lancer les nôtres !

Nous avons remarqué une perte de réseau récemment et il semblerait que le switch feuille3 ait redémarré pour des raisons inexplicables. Notre responsable du réseau a investigué mais rien trouvé d’étrange. Dans le doute, il a fait une capture de RAM du switch et vous désigne vous, oui vous, pour trouver ce qui cloche.

Nous pensons qu’il s’agit là d’un coup de nos rivaux : Imagine… Ces derniers travaillent dans le lancer de javelot, une discipline hérétique et vulgaire qui nous écœure ! Nous aurions dû faire attention et mettre des mots de passe plus forts sur nos équipements !

Trouvez le pid et le hash md5 du malware présent sur le switch

Format du Flag : 404CTF{111:891f490e5d7bdb06d90d56f8d7db405f}

Writeup #

After extracting the archive, we have a memory.elf file, which is the memory dump from the switch. I used volatility 2 and 3 to analyze it, although the final step was impossible using vol3.

The first thing to do to analyze a linux memory dump using volatility is to build a profile containing important kernel offsets so that volatility, and its plugins, are able to parse the file.

Building a profile #

To build a profile, I needed a live station running the exact same linux version as the one ine the dump. Looking through the strings in the dump, I identified this line which gave me the informations I needed:

5.10.0-cl-1-amd64 ([email protected]) (gcc-8 (Debian 8.3.0-6) 8.3.0, GNU ld (GNU Binutils for Debian) 2.31.1) #1 SMP Debian 5.10.189-1+cl5.8.0u16 (2024-01-27)

Cumulus Networks is an Nvidia company and they make public VM image of the cumulus switch OS. I downloaded it, along another vanilla Debian 8.3 VM (because I couldn’t figure out how to connect the Cumulus VM to the internet). Then I just built the Golang dwarf tool and ran it on the Cumulus VM to make the vol3 profile. I used the volatility/tools/linux to make the profile for vol2.

Finding the malware #

Skimming through the running processes gave me this:

$ /opt/volatility/vol.py --profile=LinuxCumulusx64 -f memory.elf linux_psaux

Volatility Foundation Volatility Framework 2.6.1

Pid Uid Gid Arguments

1 0 0 /sbin/init

[...]

3022 1000 1000 -bash

3089 0 0 /usr/bin/python2 /usr/sbin/smond

3095 0 0 /usr/bin/python2 /usr/sbin/ledmgrd

3096 0 0 /usr/bin/python2 /usr/sbin/pwmd

3187 0 0 /sbin/dhclient -pf /run/dhclient.eth0.pid -lf /var/lib/dhcp/dhclient.eth0.leases eth0

3306 109 113 lldpd: monitor.

3310 0 0 /usr/bin/python -O /usr/sbin/netd -d

3313 0 0 /usr/sbin/ptmd -l INFO

3314 0 0 /sbin/agetty -o -p -- \u --keep-baud 115200,57600,38400,9600 ttyS0 vt220

3316 0 0 /bin/bash /usr/lib/cumulus/sysmonitor

3317 0 0 /usr/share/venvs/netq-apps/bin/python /usr/sbin/netqd --daemon

3321 0 0 sshd: /usr/sbin/ss

3334 0 0 /usr/lib/frr/watchfrr -d -F datacenter zebra staticd

3352 109 113 lldpd: no neighbor.

3356 0 0 /usr/bin/python3 /usr/bin/neighmgrd

3397 110 118 /usr/lib/frr/zebra -d -F datacenter -M cumulus_mlag -M snmp -A 127.0.0.1 -s 90000000

3460 110 118 /usr/lib/frr/staticd -d -F datacenter -A 127.0.0.1

5226 0 0 nginx: master process /usr/sbin/nginx -g daemon o

5227 33 33 nginx: worker process

5228 33 33 nginx: worker process

6985 0 0 /usr/bin/anssible

8065 0 0 sleep 60

8119 1000 1000 less

We can see a lot of processes related to networking (frr), but one process is a little strange: anssible.

Its name looks like the automation tool ansible but nothing comes up when searching for it online.

After dumping it, I looked at the strings in the file:

pcap_create

pcap_breakloop

pcap_activate

pcap_loop

[...]

sendto

read

[...]

/usr/lib/modules/5.10.0-cl-1-amd64/kernel/drivers/net/anssible.ko

So we have:

- PCAP library, probably to listen to the interfaces

- socket usage, probably to communicate with a C2

- A kernel module

This looks awfully like a rootkit.

Anyway we have our malware so here is the 1st flag: 404CTF{6985:64c6c973e790d526486b874c95a1ef47}

Malware analysis #

Unfortunatly, I couldn’t go through the whole process of reversing it and finding the 2nd flag but I will share anyway my findings.

I had 0 experience of linux malware and at the beggining I didn’t even know it was a rootkit. Fortunatly, a few days prior to this, a colleague of mine talked about Diamorphine, a linux rootkit, and I had looked at its capabilities and how it performed his actions (in fact I read a bunch of other articles about linux rootkit to understand what it was doing).

Going back to our challenge, I also dumped the kernel module to analyze it, so let’s start with it.

The init_module function

#

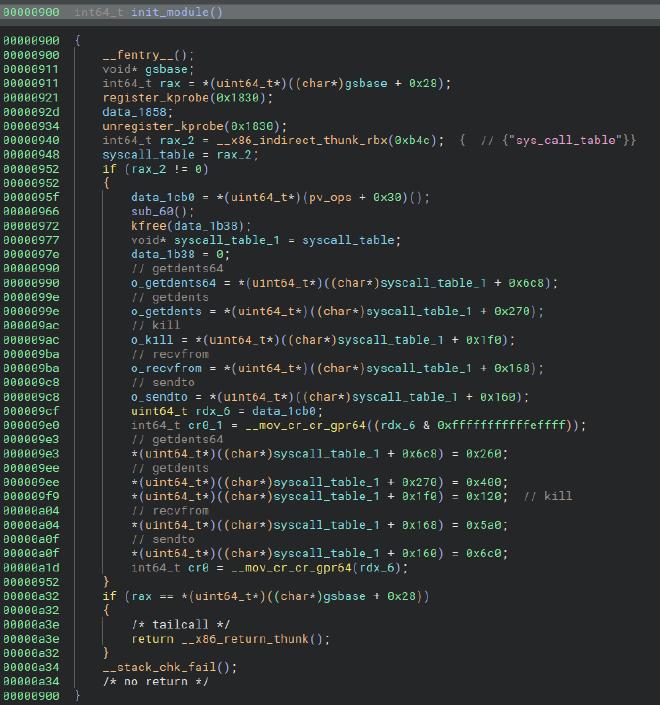

The init_module function is called when the kernel module is loaded:

Given what I learned, it was pretty clear that it was altering the syscall table to replace the handlers to some syscall functions. Just by divinding the offsets by 8 and looking at a syscall table, I identified these syscalls:

- \(\mathtt{0x6c8} \Rightarrow\)

getdents64: used to read and parse directories - \(\mathtt{0x270} \Rightarrow\)

getdents: used to read and parse directories - \(\mathtt{0x1f0} \Rightarrow\)

kill: used to send signals to programs - \(\mathtt{0x168} \Rightarrow\)

recvfrom: used to receive data from socket - \(\mathtt{0x160} \Rightarrow\)

sendto: used to send data to a socket

The kill syscall

#

From Diamorphine, I learned that kill is usually used to hide processes and even give them root permissions.

This is exactly what is done here:

kill 64gives root privileges to the calling processkill 31hides the process (it is invisible from something likeps aux)kill 63I couldn’t identify what it did

The recvfrom syscall

#

Becaus the originals offsets of the syscalls were saved, the rootkit is able to call the real recvfrom syscall and use this result before giving it back to caller.

After getting the data from the original call, this function check wheter the caller’s process is hidden (see kill 31), if not it just return the data, acting like a normal recvfrom.

Otherwise, it performs a xor of the data using the key 0xdeadbeefcafebabe (I am not sure about that part but this is what I understood) before returning the xored data.

The getdents/getdents64 syscalls

#

From what I have understood, It will remove each entries that contains anssible if the calling process isn’t hidden.

The sendto syscall

#

I haven’t had the time to look at it.

From that we have a good guess of what the rootkit is capable of, now let’s look at the malware itself.

The main function (0x555555557ea1)

#

0x555555557eb0 int32_t rax = getpid();

0x555555557eb5 pid = rax;

0x555555557ec2 if (rax == 0)

0x555555557ec2 {

0x555555557ed1 kill(((uint64_t)pid), 31);

0x555555557edb exit(0);

0x555555557edb /* no return */

0x555555557ec2 }

0x555555557ee5 wait(nullptr);

The main starts by forking itself and calling kill 31, which is intercepted by the rootkit and hides the process.

The next thing it does is checking the size of the /usr/lib/modules/5.10.0-cl-1-amd64/kernel/drivers/net/anssible.ko file, probably to ensure the rootkit hasn’t been tampered with.

It will then bind a UDP socket on port 31337 (👀) and wait for incomming connections in function at offset 0x555555557c88.

The receiving function #

After receiving data in a buffer (max len is 93), it performs some operations on the received data. Thanks to the math classes I took a few years ago, I easily recognized partial Taylor expansion sums of common functions: $\cos$, $\sin$, $\arccos$.

This is the part that lost me, after summing \(\cos^2{(a * (\text{buf}_i + k_i))} + \sin^2{(a * (\text{buf}_i + k_i))} = 1\) where \(a=0.0074799825085471268\) and \(k\) is an internal buffer to

\[ \sum_{ i = n_\text{received} }^{ \text{0x678acf} }{ \cos^2{(a * k_i) } + \sin^2{ (a * k_i)} } = \text{0x678acf} - n_\text{received} + 1 \]it verifies that this value is equal to $\text{0x678ad0}$ and that $n_\text{received} \geq 30$ which should always be true but wasn’t during my tests.

It will then do another check on the received buffer using the same kind of logic. If those checks pass, th received buffer will be used as a key to decrypt some data, then assemble some C code, compile it using tcc, write it to memory, and allow code execution from memory.

Conclusion #

I wasn’t really able to go much further but overall, I learned a lot of things about linux rootkits and their inner mechanisms, so thank you to both authors of this challenge!